“Dear Tocqueville! It presents itself to my imagination only as the asylum of peace and happiness. It’s the harbor in the middle of all the storms. I’ve never, after all, been so happy there. ”

“I thirst for Tocqueville, for our loneliness, for our intimacy, for our face to face, for everything that makes the real foundation of my happiness in this world.”

Alexis de Tocqueville – Letters to his wife Mary Mottley

Buildings history

Two towers, of uneven size, that of the grand staircase to the west, and that of the chapel to the east once flanked a small Norman house as there were so many in this land of bocage.

A third dovecote tower occupied the end of the original farmyard. It was accessed by a Norman porch that Alexis de Tocqueville had transported stone by stone around 1840 in order to open up his residence somewhat.

If we go back to the 15th or 16th century, we can easily imagine this manor house, which was at the same time a noble house of some importance since, the blindfold that surrounds it indicates it, its owner held the right of low justice, that is, he was in a way the justice of the peace of yesteryear.

In the 18th century, the manor was gradually transformed into a nice little castle. The present east façade was literally placed on the preserved part of the original old manor house, the one between the two towers, while the castle was greatly enlarged to the south.

This beginning of a total transformation that should have led to the destruction of the towers and the dovecote was halted in 1785 by the death of Catherine Antoinette of Damas-Crux, widow of Bernard Bonaventure de Tocqueville (Alexis’ grandparents).

The property was uninhabited from 1785 to 1828. Alexis de Tocqueville and his wife Mary Motley, of English descent, restored it from 1835 to 1857. Alexis wanted to have before him vast horizons, an English-style park, a small pond. He had the hedges of the surrounding bocage cut down; he had the porch of the manor moved; he replaced the manure pit on the farm with a small pond. He rearranged the commons.

In 1894-1896, Count Christian de Tocqueville (Alexis’s great-nephew) built the southern pavilion, which completed the current general aspect of the building.

The German occupation in 1940 did not leave traces in the buildings that could not be erased, apart from a few blockhouses in the surrounding fields.

More serious, however, were the consequences of the fire, which in December 1954, was to destroy about two-thirds of the dwelling house, of which, unfortunately, almost all of the oldest part of it. Nevertheless, the library, a former work office of Alexis de Tocqueville, and the chartrier containing all the family papers were saved. Count Jean de Tocqueville and his two daughters immediately decided to devote all the family resources to the recovery of the ruins.

Recently, the pavilion has been completely redesigned with all the modern comforts to be offered as a cottage.

The Owners

A first mention of Tocqueville’s dwelling exists around 1200; the owners were successively the families of Hennot, Mesnil, the Verrier.

These belonged to the family that was to give two centuries later the famous astronomer of Saint Lo (1811-1877) who discovered the planet Neptune.

The castle is currently in the heritage of the Clérel, whose ancestor is said to have been a companion of William the Conqueror during the conquest of England following the Battle of Hastings (1066).

They obtained it by exchange with the Verrier in 1661. The Clérels went through the Revolution of 1789 without much hassle, at the cost of two concessions: the removal of the roof of the feudal dovecote (which made it unusable) and the black smearing in all the books of the library, the words roy and the coats of arms fleur de lysés.

Alexis de Tocqueville said :

“You see this tower without a roof: it was my grandfather’s dovecote. He maintained three thousand pigeons there. No one had the right to kill them, and no one in the commune could have any other pigeons. In 1793, when the peasants were the masters, they did no harm to the rest of our property. We had lived among them for centuries as protectors and as friends; but they rose en masse against the pigeons, killed them to the last and put the tower in its present state. »

============================

Note the inscription on the pediment of the main entrance door:

“HOSPES INGREDERE BONI VULTUS ADERUNT”

Which can be translated into:

“Stranger, come in here, you will find good faces to welcome you”

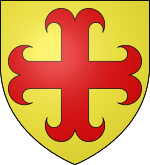

Above are two coats of arms:

On the left, the Clérel family :

« D’argent à la fasce de sable accompagnée de trois merlettes du même, rangées en chef et de trois tourteaux d’azur ordonnées 2 et 1 en pointe. »

On the right, the Damas-Cruz family:

« D’or à la croix ancrée de gueules »